Prohibition -- When liquor was outlawed, many looked the other way

Monday, December 13, 2010

Carrie Nation, with hatchet and Bible.

For the period of the 1920s, the United States banned the manufacture and sale of intoxicating beverages. This was the "Noble Experiment," or Prohibition, which was the law of the land from 1919-33. Alcohol consumption was generally on the rise from the time that white men settled in the U.S., even though at every turn there were efforts to ban intoxicating drinks. As early as 1657. the General Court of Massachusetts banned the use of "rumme, strong water, brandy, and wine." Even so, the general interpretation of the law was that drunkenness would be punished, not the moderate use of spirits.

From the beginning there were temperance societies that advocated banning all use of alcoholic beverages, maintaining that most, if not all, of man's shortcomings could be traced to the "Evil Rum." They might have had a point. In 1830 the average American household consumed 1.7 bottles of "hard liquor" per week! This is 10 times the amount of liquor consumed by the average American household in 2010.

Through the 1800s, temperance (moderation) parties increased in number, and the Prohibition Party became a strong political force in a number of states. The Woman's Temperance Christian Union gained many supporters. Kansas was the first state to outlaw alcoholic beverages under its constitution (and the last to repeal those laws, 1881-1948). One of the leading figures promoting constitutional change was Cary Nation, a member of the Kansas WCTU, who waged a one-woman crusade to stop the sale of liquor. Cary, whose first husband was an alcoholic who died very young, would enter a saloon, scold the proprietor and his customers, then proceed to smash the bar's bottles of liquor with her hatchet. The hatchet became the symbol of the prohibitionists. Other activists, almost entirely women, would enter a saloon en masse, attempting to stop the sale of spirits with singing, praying, and lecturing the owner and patrons.

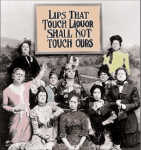

A popular WCTU poster.

Finally, in 1919, the United States entered a new age, when 36 states approved the 18th Amendment to the Constitution. Over President Wilson's veto, Congress passed the Prohibition law, popularly known as the Volstead Act. This act spelled out the definition for alcoholic beverages, and the penalties for producing them. In the early years of Prohibition these laws, though in place, were largely overlooked by law enforcement agencies. In 1925 there were as many as 100,000 "Speakeasy Clubs" (illegal saloon/supper clubs) operating in New York City alone.

It is generally agreed that Prohibition did cut down on the amount of intoxicants sold in the United States, but, it led to a general breakdown in the moral values and a shift in crime in this country. For instance, before Prohibition, Organized Crime (Mafia) had been primarily in the business of robbery and extortion. After Prohibition went into effect the Mobs were the primary sources for the manufacture and distribution of illegal liquor in the United States. This often created a strange spectacle on political platforms -- that of representatives of the WCTU and other Pro-Prohibition organizations on the same stage (and funded by) members of organized crime syndicates, who considered Prohibition good for their business interests.

There was a general flaunting of the law throughout the land. The 1920s, the "Roaring '20s," with the speakeasy clubs, the flappers, and jazz, are viewed today as an age of excess, and loose morals -- fun for some, but not so good for our country. When the rival gangs in the cities went to war with one another over the control of certain segments of the liquor trade (the Valentine's Day Massacre in Chicago for instance), the fun was considerably diminished.

In 1932, Franklin Roosevelt made the repeal of the Volstead Act one of the planks in his political platform, citing lost jobs and lost tax revenues, plus the rise of crime in the country. In March 1933, one of his first acts as president was to sign into law the Cullen-Harrison Act, which allowed the manufacture of certain alcoholic beverages. The Anheuser-Busch Co. marked the occasion by sending an old fashioned beer wagon, pulled by six giant Clydesdale horses, to the White House with a complimentary case of beer for the president. In December of the same year the 21st Amendment to the Constitution was ratified, repealing Prohibition (20th Amendment).

During Prohibition, "bootlegging," the dealing in various illegal liquor activities, did not seem to have the same stigma attached to it as did other crimes.

In Nebraska, Germans made up more than 50 percent of the foreign-born population. Their view that beer was a food, not just an alcoholic drink, resulting in wide spread discontent with Prohibition.

There were a number of large breweries and distilleries in the state, which had employed a great number of people before Prohibition and these jobs were missed. People went to creative lengths to skirt the law.

The home my folks bought in Plainview had been built by a prominent business man.

It had an attached garage (rare in homes of the '20s). After we moved in we discovered a secret little room in the attic. We were told that the former owner regularly motored to Canada, bringing back a six month's supply of liquor, which he unloaded inside the garage and stored in his secret storeroom.

Another time, some of my friends and I discovered a secret stash, where liquor had been stored in a woodpile. This was on the property of a respected farmer.

In McCook, there was considerable interest in the underground rooms that were uncovered when the new sidewalk was put in during the Keystone renovation project. Whether these areas were secret or not is unknown, but it is known that the Keystone, in its heyday as a hotel was a place where one could obtain liquor during Prohibition.

Ray Search told of one bootlegger, who had a sliding compartment in the floor of his car. He would park over one of the coal shoots and unload illegal booze to a confederate who worked at the hotel. The main bellhop at the hotel was the fellow who could line up a thirsty customer with a trusted bootlegger.

One time a revenue agent stopped at the hotel and asked to buy booze from the head bellhop. Evidently, the bellhop suspected that the customer might be an agent. He arranged that the agent would meet his supplier on the DeGroffs corner of B Street on a busy Saturday night. When the two met the contact asked for the money in advance, saying he would have to go get the liquor. When the agent objected, the supplier gave him a box, which he said contained a new pair of shoes, for collateral. The contact man did not come back for a very long time, so the agent opened the box.

Instead of shoes, the box contained his liquor, as promised, the contact man now long gone and no arrest could be made.

Since Kansas remained "dry" long after Prohibition was abolished most places, Southern Nebraska harbored illegal stills for years. Recently the remains of one was discovered between

Indianola and Danbury. As late as the 1960s a large active still was discovered in the sandhills, north and west of McCook -- for the Kansas trade.

Source: Prohibition: A lesson in futility -- Prohibition of the '20s.