Experts: Flash drought to continue

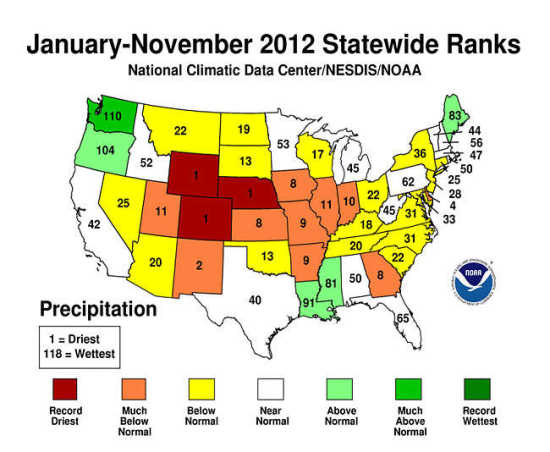

LINCOLN, Nebraska -- The drought that swept across wide areas of the United States in the past year was historically unusual in its speed, its intensity and its size, climatologists at the National Drought Mitigation Center at the University of Nebraska-Lincoln said this week.

And, they said, those dry conditions are expected to last at least through winter: Forecasts show little hope of quick improvement, deepening the negative effects on agriculture, water supplies, food prices and wildlife.

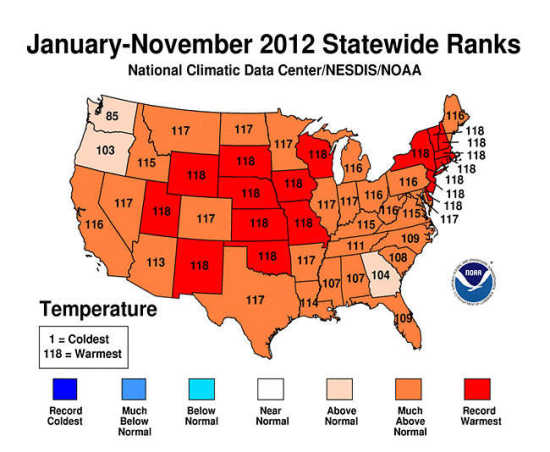

"We usually tell people that drought is a slow-moving natural disaster, but this year was more of a flash drought," said Mark Svoboda, a center climatologist and an author of the weekly U.S. Drought Monitor. "With the sustained, widespread heat waves during the spring and early summer coupled with the lack of rains, the impacts came on in a matter of weeks instead of over several months."

The result, according to year-end Drought Monitor data: More than 60 percent of the contiguous 48 states and 50 percent of the entire country was in severe to extreme drought for significant portions of 2012, Svoboda said. This year marked the first occurrence in the 13-year history of the monitor that all 50 U.S. states and Puerto Rico experienced drought. In the past few months, it has receded slightly in the Midwest but remains entrenched in the Great Plains.

'ALMOST THE PERFECT STORM'

While the current drought has been brutal, it has been short from a historical perspective, said Brian Fuchs, also a monitor author and center climatologist. But unique conditions earlier in the year set the stage for the unusually intense and widespread drought.

"It was almost the perfect storm this year, a mild winter without much precipitation and with early green-up, so plants were using moisture a month or more earlier than usual," Fuchs said. "Then we had the heat of the summer, plus the fact that it was dry from mid-May onward."

Earlier this year, forecasters expected an El Nino weather pattern would be in place, bringing rain to the southern United States. But the pattern fizzled, leaving North America with neutral -- neither El Nino nor La Nina -- conditions, making it difficult to anticipate a single large-scale weather pattern for this winter.

Neutral conditions indicate a lack of an established weather pattern, likely meaning big swings in temperature and precipitation across the country through the winter, Fuchs said. Many parts of the country would need a tremendous amount of snow and a very long winter to start putting a dent in this year's moisture deficits. The odds for that type of winter to occur are roughly two in 10 at best, according to Al Dutcher, Nebraska state climatologist.

EFFECTS OF THIS YEAR'S -- AND NEXT YEAR'S -- DROUGHT

The first wave of drought impacts has been agricultural: The U.S. Department of Agriculture's Risk Management Agency said Dec. 10 indemnity payments for 2012 were at nearly $8 billion. The winter wheat crop outlook across the Great Plains has been reduced, and ranchers are scrambling to find feed for cattle. Hay prices have risen, likely meaning bigger grocery bills as meat and dairy prices climb in response.

The second wave of impacts is often hydrological: Lack of water flowing down the Missouri River is prompting states along the lower Mississippi to challenge the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers' river management, anticipating hardships for the river navigation industry and all who depend on it to deliver commodities to markets, and some of the Great Lakes are at or near record lows. Fuchs said it is likely those basins are going to be fairly dry through winter and into next year.

As of late December, 82 percent of the Missouri River basin and the upper Mississippi basin and a third of the lower Mississippi basin were in moderate drought or worse, drought center data showed.

Fuchs said that while severe hydrologic drought hasn't yet hit the majority of the country, those who depend on older or single wells should check reliability now, before hot weather and the growing season increase water use. Farmers and ranchers may also consider potential savings from using better irrigation technology and no-till practices.

"In the Southeast and southern Plains, multiple years of drought have resulted in widespread hydrological drought issues with water supply and water quality as well as with declining storage and water tables," he said.

"In areas where the drought has been shorter, such as in the Midwest and Plains, there are some water systems that are already under stress and more impacts related to hydrologic drought will develop as the drought continues."